Yew

YewThe yew is a tree with rough bark,

hard and fast in the earth, supported by its roots,

a guardian of flame and a joy upon an estate.

Anglo Saxon rune poem

From Wikipedia article on the rune Eihwaz

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/EihwazI chose to write about the yew for Winter Solstice, standing as it does between the six weeks which I am calling the tide of the berries (Halloween to Yule) and the six weeks of evergreens (Yule to Candlemas), since the yew has both berries and evergreen foliage (although the berries are actually fruit and the yew is not a true conifer). It is a sacred tree, featured over centuries and cultures, in myth and folklore, and symbolizing both death and rebirth, thus resonating with the message of the Winter Solstice when in the midst of darkness the Sun is born again.

There is a great yew hedge over 14 feet high between two houses down the street from my apartment building on Capitol Hill. A few weeks ago it was dotted with red fruit and made the perfect Christmas statement. The fruit of the yew is called an aril. They look like soft, squashy red gumdrops with a hole in one end. Although many people believe they are poisonous (the foliage and bark of the yew are), the berries are edible, although the hard seed inside is not. Birds love the fruit and that’s how the yew is distributed, as the seed passes through their digestive tracts intact.

There’s a lively discussion about whether it’s safe to eat the arils on the Plants for a Future site but it seems that as long as you don’t eat the seed, you should be OK. The tastes is described as sweet, possibly sickly, and the texture as snotty (not totally appealing, is it?).

http://www.pfaf.org/database/plants.php?Taxus+baccata

Nevertheless, I had gotten up my nerve to try one and visited the yew hedge yesterday. Imagine my surprise when I discovered that every fruit was gone. I even peered inside the hedge to see if I could find one that had been protected, but they were all gone, except for a few dusty ones scattered on the ground underneath the yew. Either the birds or the high winds had beaten me to it.

The other yew in my neighborhood was in front of my apartment building, making an interesting trinity with a hawthorn and a holly (in my neighborhood, hollies are often planted beside hawthorns and I wonder why). At some point, someone cut down the yew but yews are hard to kill. It is now putting out many small branches, forming a low hedge all around the trunks of the other trees. I don’t recall ever seeing fruit on this yew, so it must be a male tree.

While I was researching for this article, I found so much information on yews, that I can’t possibly summarize it. In fact, there is a whole book on yews:

The Sacred Yew by Anand Cheton and Diana Brueton which I was able to get out of my public library. It focuses on the work of Allen Meredith, who, spurred on by dreams, made it his life work to learn about and protect the ancient yews of England. Another big fan of yews, is one of my favorite tree writers, Fred Hageneder, who founded a society, Friends of the Trees, to save endangered yews in England. It seems to be that kind of tree.

Yews are members of the genus Taxus, which contains only eight species. It grows in temperate climates as far south as Sumatra and Central America. The common yew is

Taxus baccata.

Baccata means berry.

Taxus comes from the Greek word for arrow, a word that also is the root of poison. There’s some speculation that arrows were poisoned and thus the connection but it seems just as likely to me that it refers to the toxicity of the plant itself. The leaves are so poisonous that eating as little as 50-100 grams of chopped leaves would be fatal to an adult. I found a website about poisonous plants and horses that mentioned that yew was so toxic that horses were frequently found dead with yew leaves still in their mouths.

The name yew itself has an interesting history that goes back to the Germanic

iwe (

iwa) which is related to

ihhe, the word for first person singular. In Anglo Saxon ih means both I and the yew triee.

Iwe is also related to

ewi which means eternal. The 13th rune in the old Norse rune alphabet, the old futhark, is called

ihwa or

eiwaz meaning yew and it represents death and rebirth. There is also a rune,

yr, associated with the yew in the younger Scandinavian rune set. It looks like the old Stone Age symbol for the Tree of Life and as a result, some scholars believe that Yggradasil, the tree on which Odin hung himself for four days and nights, before bringing back the runes, was a yew tree. His spear was made from a branc

h of the tree.

The needles of a yew tree are about ½ to 1 inch long, flat, dark green above and pale green below. The tree flowers in spring (mid-February to mid-March) and both male and female trees flower. Gilbert White complained about the ancient yew in the churchyard of his parish at Selborne in 1789 which had the habit of throwing out pollen in April (as male yews will) all over his parishioners.

The yew has an interesting growth pattern. It grows very slowly, at about half the rate of other trees, and thus lives a long time. The interior of the trunk often crumbles so the trunk becomes hollow. Thomas Pakenham, who photographed many beautiful old yews in his marvelous book, Meetings with Remarkable Trees, describes the hollow interior of the old yew at Crowhurst thus: “New wood in an old yew tree accumulates like coral. The old room now resembles a cave flowing with pink fretted rock.” Sometimes an aerial root grows down inside the hollow trunk and becomes a new trunk, thus the imagery of life in death. Yews also grow outward because branches sprout new roots when they hit the ground, thus creating tangles of branches and trunks.

There is much dispute about the age of yews since they cannot be dated like other trees (by counting rings because the oldest wood, in the interior of the tree, is missing). Instead scientists study records showing the girth of the tree at various historical periods and estimate the age by noting the slow rate of growth. Estimates range from 1,500 to 2,000 years old. This poem provides a glimpse of their great age:

The lives of three wattles, the life of a hound;

The lives of three hounds, the life of a steed;

The lives of three steeds, the life of a man;

The lives of three eagles, the life of a yew;

The life of a yew, the length of an age;

Seven ages from Creation to Doom.

Nennius,

Seven Ages

Yew wood is fine-grained, water resistant and so hard it’s sometimes called ironwood. Thus the oldest wood artifact found is a yew spear, found at Clacton in Essex, which dates from 250,000 BC. To give you an idea of how long ago that was, a younger yew spear (from 200,000 BC) was found in lower Saxony lodged between the ribs of a straight-tusked elephant. The oldest musical instruments that have survived are made of yew, as are most of the runic talismans. According to Hageneder, when the wood foundations of buildings in Venice were replaced in the 1950’s the yew beams were still in such good shape they were sold for timber.

Yew was the favorite wood for making bows. Two yew bows were found in the Somerset Levels that date to about 2700 BC. A yew longbow was found with the Neolithic corpse, known as the Iceman, found on the Italian-Austrian border. His bow was 6 feet long, although he was only 5 feet, 2 inches tall. This bow may be even older, possibly dating back to 3,500 BC.

The yew longbow became famous in the 13th and 16th centuries when Welsh archers using yew bows won battles for the English against the Scots, and later the French. The bows were designed with the heartwood on the inside and the sapwood on the outside, so that the heartwood stands up to the compression while the sapwood allows the bow to stretch. During this time period, the English so depleted their own yew stands that they began importing yew, first from Spain, then from the Hanseatic towns of the North and Baltic Seas.

Yews have featured in history for centuries. Robert Graves says that the yew is a death tree, sacred to Hecate in Greece and Italy. When black bulls were sacrificed to Hecate, so ghosts could lap their blood, they were wreathed with yew.

Several Celtic tribes named themselves after the yew tree, including the Eurobones and Eburovices in Gaul. Possibly yew is the source of the word Iberia as in Iberian peninsula. Simon mentions a deity named Eburianus in the Iberian peninsula whose name, noted on a tombstone, derived from the same root as yew. There was a tribe of Celts called the Eburoni (the Yew People) in Portugal. Caesar in the Gallic wars wrote that the chief of the Eburones poisoned himself with yew rather than submit to Rome. It’s possible yew-worshipping Celts were the first invaders of Ireland and named it after the tree as Ierne, Yew Island.

The Yew of Ross is one of the Five Magical Trees of Ireland. Its qualities are described in the Rennes Dindshenchas:

Tree of Ross, a king’s wheel, a prince’s right, a wave’s noise, best of creatures, a straight firm tree, a firm strong god, door of heaven, strength of a building, the good of a crew, a word pure man, full great bounty, the Trinity’s mighty one, a measure’s house, a mother’s good, Mary’s son, a fruitful sea, beauty’s honor, a mind’s lord, diadem of angels, shout of the world, Banba’s renown, might of victory, judgement of origin, judicial doom, faggot of sages, noblest of trees, glory of Leinster, dearest of bushes, a bear’s defence, vigour of life, spell of knowledge, Tree of Ross!

Giraldus Cambrensis, the medieval historian (and my distant relative) noted the ubiquity of yew trees in Ireland in the 1100’s: “Yews are more frequently to be found in this country than in any other I have visited but you will find them principally in old cemeteries and sacred places, where they were planted in ancient times by the hands of holy men, to give them what ornament and beauty they could.”

Chetan and Brueton in their book,

The Sacred Yew, hypothesize that yews were planted in neolithic times on sacred sites and on top of barrow graves as symbols of death and life. Early Christian missionaries recognized the sacred nature of the trees and built their churches near them. Monks and hermits were also said to live in the hollows of yew trees, again a recognition that yews marked sacred sites. In tenth-century Wales, the penalty for cutting down a consecrated yew (does that mean a yew growing in a churchyard?) was one pound, more than most people earned in a lifetime.

Yews are often found in growing in churchyards and cemeteries. Some ancient Welsh churches were ringed by circles of yews. After the Norman Conquest, cemeteries were more likely to be rectangular and marked with a yew in each of the four corners. Chetan and Brueton note that the oldest yews were usually male trees planted on the north side of churches. The north was considered the direction of death.

Yews were used in place of palms on Palm Sunday in Britain. Some folklore suggests that it is dangerous to bring yew into the house (it will bring death into the family) but it is also mentioned as an appropriate foliage for winter holiday decorations.

The association with yews and death is a strong one. Shakespeare called the tree the double fatal yew and made Hamlet’s uncle poison the king by pouring its juice (hebenon) into his ear. The 19th century English poets loved to use yews as symbols of melancholy and gloom, as in this poem, “Yew Trees,” by Wordsworth:

There is a yew, the pride of Lorton’s vale,

Which to this day stands single in the midst

Of its own darkness as it stood of yore …

Of vast circumference and gloom profound

This solitary tree! – a living thing

Produced too slowly ever to decay;

Of form and aspect too magnificent

To be destroyed.

Or in this reference in Keats’ “Ode on Melancholy,”

Make not your rosary of yew-berries,

Nor let the bettle, nor the death moth be

Your mournful Psyche, nor the downy owl

A partner in your sorrow’s mysteries.

Speaking of owls and yew trees, the Pacific yew is the habitat of the northern spotted owl, that little bird seen as the bane of loggers since logging was forbidden in areas where this endangered creature lived. Later it was discovered that the bark of the Pacific yew was a good source for taxol, a compound proved effective in combating cancer. The Pacific yews became as endangered as the owls until scientists learned they could synthesize the compound from the leaves. .

In Japan the yew tree (

taxus cuspidate) is connected with the creator gods who live on mountain tops and is called

ichii, the Tree of God. In the country of Georgia, the yew is called the Tree of Life.

References:

Chetan, Anand and Diana Brueton, The Sacred Yew, Penguin/Arkana 1994

Graves, Robert, The White Goddess

Pakenham, Thomas, Meetings with Remarkable Trees, Random House

Hageneder, Fred, The Meaning of Trees, Chronicle 2005

Fred’s website

http://www.spirit-of-trees.net/Murray, Colin and Liz, Celtic Tree Oracle,

Simon, Francisco Marco, “According to Religion and Religious Practices of the Ancient Celts of the Iberian Peninsula,”

http://www.uwm.edu/Dept/celtic/ekeltoi/volumes/vol6/6_6/marco_simon_6_6.htmlWikipedia article on yew:

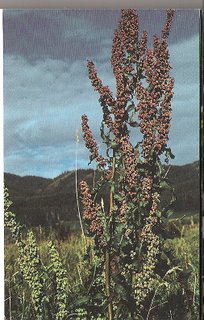

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxus_baccataPhotograph of a Yew from the Ancient Yew Group which includes among its members Fred Hageneder

http://www.ancient-yew.org/home.shtml